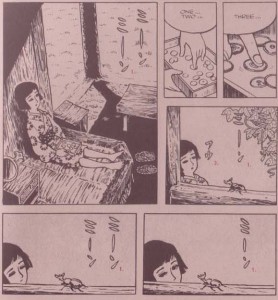

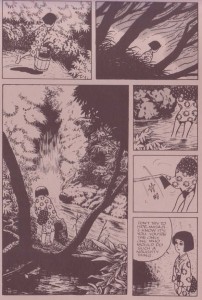

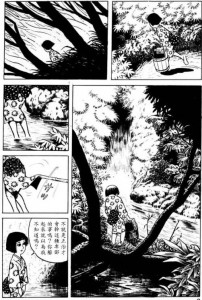

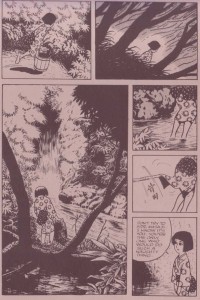

Red Flowers. Sayako Kikuchi is lying in the shade of her tea shop. It is a warm summer day and far too hot to count the meager takings from the morning. There is the sound of cicadas in the background and we gaze up at this incessant activity with the girl. The tree before us is as firm and immovable as nature itself. The tea shop is cradled in its grasp, nestling in a womb-like clearing with tendrils and fruit running through its thatched roof.

The girl is drowsy…

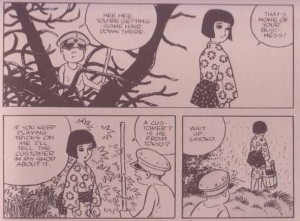

…audacious in her business dealings…

…attentive to her customers…

…indifferent to her classmate’s (Masaji) playfulness…

….and surprised by his care and attention.

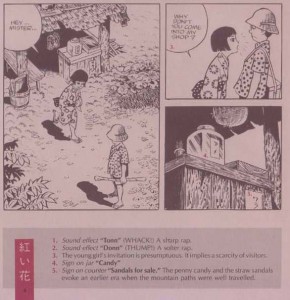

She is perhaps 12 or 13. Her classmate, two years younger. Each moment is described with a restrained elegance: her body leans forward intrusively as she accosts the passer-by; her eyes cast downwards in a slight frown as she describes Masaji; and she unobtrusively waves a small fan as she converses with her customer.

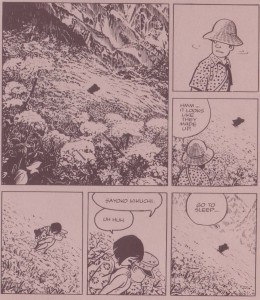

These moments of interaction are punctuated by the silent, entwining forest. The girl, her face turned away from us, is seen rushing through these woods, the branches like arteries and veins enfolding her as she sets about her work.

The Sound of the Mountain. The insects are also “screeching” at Shingo’s rural retreat in Yasunari Kawabata’s famous novel, The Sound of the Mountain. There are “locusts on the trunk of the cherry tree…He had not known that locusts could make such a rasping sound.”

Shingo is old and beginning to forget, just as Sayoko Kikuchi is about to remember that which he is forgetting. His wife’s beautiful sister, an unattainable and long dead first love, is transfigured in his daughter-in-law, Kikuko, a young woman with whom he has an inexplicable bond. They dote on each other with the shyness of a new couple, an affection altogether absent between Shingo and his wife. It is a forbidden love which is never realized except in his subconscious. The very idea repulses him as it would the young couple of Tsuge’s tale.

Shingo’s path through the story is littered with failure and regret. The garden attached to his house has partaken of his melancholy and is a surrounded by a variety of trees: a great gingko still sending out buds despite its age and also a cherry tree, weak and drooping after a storm. Broken amaranth blossoms lie in the street outside his house, the petals withered, “the stems dried and turned dirty and gray. Shingo had to step over them on his way to and from work. He did not like to look at them.”

It is autumn when Kawabata’s novel begins and it is autumn again when it closes (a death forestalled), the memories as relived through Kikuko still visible and palpable even as the novel draws to a close:

“There was an indescribable freshness about the line from her jaw to her throat. It was not the product of a single generation, thought Shingo, somehow saddened….That line from jaw to throat spoke first of maidenly freshness. It was beginning to swell a little, however, and that maidenliness would soon disappear.”

Time has been kind to Shingo as have the seasons. Both have stood still within the boundaries of Kawabata’s book. A series of minor disasters (his son’s affair, Kikuko’s abortion, an illegitimate child) have been rectified by the vagaries of fate. Still, it is August, the “autumn insects” have begun to sing and he is already starting to forget.

In these stories, Tsuge and Kawabata reveal a nostalgia for a vanishing era and its associated values. Senility, death and the modern world wreak havoc on Kawabata’s women even at their most idealized. That chimeric and flawless past never to be recaptured in Shingo’s deteriorating memories.

Those bygone times are distant, secluded and preserved in Tsuge’s comic. His heroine’s kimono and domesticity in sharp contrast to her strangely modern visitor; her innocence, strength and grace untarnished by contemporary life. The pace of living is slow and measured, the sound of the forest ever present and attended to by its single resident. Sayako is always seen amidst this lushness, color and overflowing abundance. Tsuge is utterly convinced of the value and nobility of her life, that it can and should exist together with the overwhelming changes of modernity.

Her classmate, Masaji, stands apart from this world in the middle of a crop of gnarly branches, raw and naive as those naked shoots in his lack of awareness.

The old army cap he wears originates from some buried history, its significance set aside, forgotten or disremembered in this pastoral landscape.

Having guided the traveler to a suitable fishing spot (a gourd-shaped stretch of water), Masaji leaves him in search of Sayako, finding her at the edge of the river at her toilet. Her face is once again turned away from us as it once was when she skirted the forest collecting water. The red flowers of her menstrual discharge fill the young boy’s eyes like a vision, a blossom hitherto unnoticed, now barely grasped by his awakened mind.

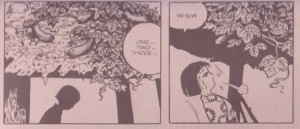

Soon she is resting in the shade of the tea house, just as she was when we first saw her at the start of Tsuge’s tale; now in more quiet repose under her classmate’s attentive gaze.

Wonderment and responsibility have begun to replace the frivolity of Masaji’s childhood. He tells her to close up the shop and go home and she agrees. The last we see of them is a mingled silhouette in the distance as Masaji carries his friend home. It is not merely Sayako who he carries on his back and urges into a fitful sleep towards the close of this short story but the entire weight of her world; a beautiful, painful and expiring dream.

More on Yoshiharu Tsuge

Domingos on Yoshiharu Tsuge

Gilles Laborderie on Tsuge’s Munô no Hito

Beatrice Marechal on Tsuge’s oeuvre (from The Comics Journal 2005 Special Edition)

Matthias Wivel on Tsuge’s translated works

A review of Tsuge’s Numa at Dusty Recollections

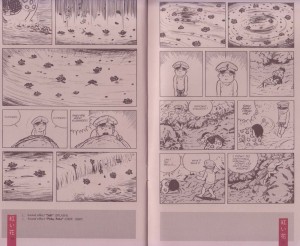

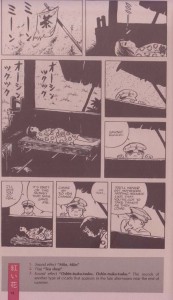

A short note on an old issue. The only English version of “Red Flowers” is an object lesson in why manga should not be flipped. The first example in particular demonstrates how Tsuge’s page composition and the flow between panels have been totally compromised. Original layouts are from a Chinese version of Tsuge’s comic.

Example 1

Page 2 top tier, read from right to left (original)

Page 2 top tier, read from left to right (flipped; from Raw Vol. 1 #7)

Example 2

Page 2 bottom tier, read from right to left (original)

Page 2 bottom tier, read left to right (flipped; from Raw Vol. 1 #7)

Example 3

Page 5 read from right to left (original)

Page 5 read left to right (flipped; from Raw Vol. 1 #7)

Fine piece, Suat!

I agree; this is great.

The comparison between Tsuge and Kawabata is very interesting. It sounds like both use a lyrical portrayal of women as a way of symbolizing times past — the nostalgia is very gendered. Age difference seems very important in both too; the gap in ages makes an actual romance verboten, tying the women more closely to the idea of an irretrievable past.

Haven’t looked through all the other reviews yet — does anyone talk about gender is his work?

Thanks! I don’t think there’s anything very specific about gender in those reviews though Matthias did mention the use of gendered symbolism yesterday. As you know, it’s a huge part of Kawabata’s work and accusations of misogyny are reasonably common as far as reviews of his novels are concerned.

Both their individual styles have often been compared with haiku and I suppose you could come up with a nice article showing how elements of kigo and kireji can be found in something like “Red Flowers”.

There’s actually very little written about Tsuge’s work in the English language online which sort of tells you where we’re at as far as translated manga & manga criticism is concerned.

I don’t know anything about Kawabata except what you’ve written! Nor anything about Tsuge either. Has Bill ever written about Tsuge? It doesn’t look like Adam Stephanides (who also reads Japanese) has anything online that I can see….

A Google search brings up this: Randall, Bill. “Hey Kids! Gekiga (part 2)” / by Bill Randall. p. 107-111in The Comics Journal, no. 245 (Aug. 2002).(Lost in Translation) — Examines the works of Yoshiharu Tsuge and Imiri Sakabashira.

I love Sound of the Mountain. Probably my favorite Kawabata novel.

I think you could put a number of Ozu films into the same arena of relating woman in traditional roles with a vanished past, but Ozu’s films are sympathetic to the changing roles and interactions between the generations in regards to the modernization of women/gender roles.

(How’s that for vague and generalizing commentary?)

I think the comparison to the films of Ozu in this case is apt. One of his finest, “Late Spring”, has a generational relationship at its heart as well though this time between a father and his daughter. As Derik implies, it’s more about embracing the future while not forgetting the past.

If Bill passes by these parts, we should get his permission to reprint that TCJ Tsuge article. It contains a review of one of Tsuge’s collections called, Nejishiki, and an interpretation of Screw-Style.

Excellent article.

One quibble- you state that the panels at the end are an example of why “flipping” artwork significantly alters and damages compositions. The example you show isn’t flipped, though, it’s cut-and-reshuffle method popularized by Drawn and Quarterly. IMHO this is extremely damaging, whereas mirror-imaging (flipping) the whole page doesn’t change the compositional intent at all, assuming your intended audience reads primarily from left to right. Maybe what we need is a good word for this other type of production decision.

I would love that, but I think Bill tends to prefer to reprint things on his own site? But maybe if he pops by he’ll be inspired to post it and then we can all link to it….

Sean: Thanks for the clarification. It may be that technology has progressed to the point that hardly anyone uses the “cut-and-reshuffle” (as good a term as any) method anymore (I think). I should add that while the RAW version is a disaster, it’s still better than nothing. If example 3 is correct (and I can’t be sure until I check my Japanese version of the story), it would appear that the editorial team may have even tried to “improve” the flow of the page. To which I would have to say, thanks but no thanks.

Suat- Unfortunately, “cut and shuffle” is how all of Tatsumi’s work has been presented in English so far- in fact, all of D + Q’s manga releases so far. The only other really prominent use of it I can think of is Blade of the Immortal. It completely changes the page to page flow where it is used. It’s not an issue of technology either (mirror imaging was done very easily in the analogue post production days)- I’m sure it was a decision made by Tsuge or RAW’s editorial staff, to avoid the dreaded “left handed characters with their kimonos tied wrong” syndrome, or because the artist was just freaked out by seeing his work flipped. Why either of those things are more important than preserving the flow of a page, who knows?

I’m hoping to do a post some time in the future about the physical issues of production and how they’ve changed over time, so in the meanwhile I’ll try not to clutter your comment section with more of this ^_^

Derik mentioned Ozu, but it was Mikio Naruse who filmed _Sound of the Mountain_.

There is a film of Sound of the Mountain!?!..

Sadly, doesn’t look like it’s available in English. I will look up the one Naruse film that is (When a Woman Ascends the Stairs).

Derik: http://tinyurl.com/34j3nxq

Sean: Thanks for the info once again. Which begs the question, why would an arts comic publisher do something so disgusting? I presume it’s either the artist’s decision or a purely commercial one since right to left reading is unnatural to the American market (like subtitles and black/white movies). I suppose I don’t really care that much when it comes to Tatsumi’s work since I’m not a big fan of it, but it can’t make anyone that happy to have the comics equivalent of Criterion do something like that.

Concerning the film adaptation of The Sound of the Mountain: while it is an interesting film in itself, it didn’t seem like a very accurate adaptation of the novel at the time I watched it. But my memory is hazy on the subject and I’ll have to view it again. And When a Woman Ascends the Stairs is worth catching as well.

Derik, on Sound of the Mountain, last week I hacked my Mac’s DVD firmware to make it region-free– shoot me an email if you’re taking the plunge.

Suat, “If Bill passes by these parts” sounds like what a cowboy would say– and I’m in Oklahoma amongst the cowboys for the week!

That said, please please please don’t dig out those old essays of mine! I’ll write a new article just as a smokescreen. 2002 Bill’s criticism terrifies me. In theory, as I haven’t reread any of it.

And I’m glad to see these pieces & look forward to digesting once I’m back home– I was actually contacted recently by a British scholar doing work on Tsuge, I’ll point him this way too.

Bill: Thanks for moseying on down :P That 2002 article reads just fine but I hope you’re not joking about the new article since Noah is going to take you at your word! Aren’t most DVD players sold in America region free by now? Also, don’t buy from the U.S. Amazon. It’s dirt cheap (17.99 pounds) from Amazon.com UK (must be selling badly). The details can be found at DVD Beaver.

Many American DVD players can be made region fee by punching in a code using the remote control. These codes can be found all over the internets. For Macs, the other option is to use “Mac the Ripper” to rip the DVD to the hard drive. It strips the region coding when doing so. For more advise, go here.

Pingback: News for new comics day | Anime Blog Online

Thanks for that Suat — enjoyed the analysis. Here’s my own take on the story for what it’s worth.

#10 Akai Hana [The Red Flowers] October 1967; Garo, 18pp.

A haunting three-hander set in the baking heat of midsummer somewhere in the mountains of rural Japan. The intense sunshine and screaming of the cicadas are repeatedly referenced, firstly in the opening half-page frame, focused on a large tree (kind of Scots pine or cedar?), bare trunk to halfway up, asymmetrical branches above with clusters of leaves/twigs?, with the brightness of the sun behind it and the sound of cicadas going miiin, miiin. Tsuge cinematically pans in on a small hut by a winding mountain trail selling tea to passers-by… of whom there cannot be many in such an isolated location. We see that eggplants and melons/mushrooms [?] are growing in the rotted thatch of its roof – or have they just been put there to dry? Abundant foliage suggests they really are growing there – using the angle and elevation to get more sun. The hut is a site of natural power and fertility, comparable to the swamp in Tsuge’s breakthrough work Numa (The Marsh or Swamp; February 1966).* And the girl working in the hut, at first seen only in silhouette, turns out to be essentially the same girl as in Numa, minus the occasionally blank white eyes. She speaks the same rustic dialect. She is even wearing almost the same yukata, though the roundels are open at the centre, perhaps dilated versions of the ones in Numa, hinting perhaps that she has blossomed a little more since then. Anyway, many hints invite us to read these two pieces as two halves of a set. Later the girl will appear once more, in Mokkiriya no Shojo (The Girl at the Mokkiriya; August 1968).

This time she has a name – Sayoko Kikuchi. She is sitting in the hut, exhausted from the heat, trying to count the coins in her cash box. There are only seven, but she cannot get past three. A stag beetle wanders by, flying away when she taps the sill of the hut’s glassless window.

A traveler arrives – a young man with a fishing rod, clearly related to the young man with the gun in Numa. Male outsiders, probably urban, bearing phallic symbols of hunting and fishing. She approaches and orders him into the tea hut. Again like the girl in Numa, she combines a delicate frailty with a surprisingly direct, almost peremptory style in addressing a man. (We know she is modeled on one of the servant girls Tsuge met on his hot spring travels – that mix of the delicate and the coarse appealed to him.)

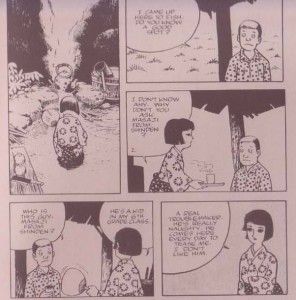

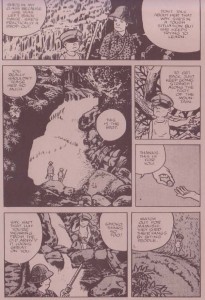

He orders tea and asks if she knows any good fishing spots. She doesn’t, but recommends a little boy called Masaji, very lazy and badly behaved but with good fishing knowledge. While he drinks his tea, she runs down to the river to fetch water. Masaji is hiding in the bushes and raises the hem of her yukata with a bamboo pole. Unfazed, she tells him to go and help the traveler. Masaji leads the traveler down to a fishing spot near a marsh (sawa, not numa). At the base of the towering mountain, just above the water, an abundance of red flowers is growing. They look like roses. Masaji surprisingly tells him that some of the iwana fish [char] eat the flowers to improve their bowel movements.

As they walk along, the traveler asks Masaji about the girl. Masaji says her father is a drunkard [Yoi-yoi], and she often misses school to work in the tea hut. She is two years older than him but in the same class at school because she has been kept back twice. The traveler tells him to avoid bullying her. Notice how he reverses the tone of Sayoko’s comments, in which he was the bad pupil. We recall Sayoko’s difficulties with couting. Could she possibly even by slightly retarded?

They come to a good fishing hole, and the traveler gets directions home and pays Masaji a coin for his help. He tells Masaji he looks good in the ancient, adult-size military cap he is wearing. Masaji says Sayoko was the first to praise his hat. Then he waves farewell and warns the traveler of the mamushi snakes [pit vipers] that will bite people “to extract their teeth” (ha o nuku tame). As with the constipated fish, this does not seem to have any relation to biological fact. Perhaps these nuggets of homespun wisdom relating to classic phallic symbols indicate Masaji’s fumbling attempts to understand the first stirrings of his own sexuality.

Masaji hurries home – with his local knowledge and effortless progress through difficult terrain he reminds us of Shirato Sanpei’s miniature ninja Sasuke or Hachimaru in Chiba Tetsuya’s Shidenkai no Taka… and ultimately of Kintaro, Momotaro etc. His outsize military cap may be a humorous reference to the absurdity of militarism in a defeated nation [a stretch?]; or perhaps of the little boy’s longing to be a powerful man.

As he skirts the river Masaji notices Sayoko, clearly not feeling well, washing her nether parts in the river. Her fatigue and discomfort stem from her period – perhaps her first ever period. As she squats in the river, lots of the red flowers fall from their stems into the river, symbolic splashes of blood – whole heads as well as loose petals. Masaji looks on spellbound – “Flowers! Flowers! Red flowers!” The camera dwells on the flowers for six frames, as they go over some rapids and into an eddy.

Masaji then sees Sayoko collapsed on the bank. He goes to help her but she waves him away “Don’t come near! I have stomach cramps.” He runs away in confusion. Next page. Sayoko has made it back to the hut. She is lying on her back, exhausted, maybe ill. Masaji rouses her by offering to share the 20 yen he got from the traveler with her. She counts out the change, then slumps down again, barely conscious. He suggests shutting up the shop and going down the mountain: she does not respond. He sits outside the hut, wondering why she ignores him. The cicadas are heard again, while the sun, now lower in the sky, blazes through a gnarled old tree with dense undergrowth.

Last page: Hero is walking down the mountain, heading for home. In the distance he sights Masaji carrying Sayoko on his back through a vast field of cow parsley / noraninjin (?). “Looks like they’ve made up…” he says to himself. Camera zooms in on Masaji and Sayoko. He says “Hey, Kikuchi Sayoko…” She sleepily says “yes?” The camera pans out again, reducing them to a distant little silhouette. “Go to sleep” he says.

Commentary: The hero is absent from the story at the beginning and end. The sequence on the final page is telling: we start with the hero; he glimpses Sayoko and Masaji in the distance; then we move in to the two children. We hear them talk, though they are much too far away for the hero to hear them. Clearly, the camera has abandoned him, preferring to stay in the rural and archaic world of the two children.

He is also absent during the climactic scene where the little boy gets to see the red flowers falling into the river while the girl washes herself. The two children seem to be part of a closed system, into which he briefly intrudes. They are “natural” children, surrounded with vegetation, in a womb-like valley of intense fertility and innocent nascent sexuality. The little boy’s references to flower-eating fish and sharp teethed snakes suggests a growing phallic awareness. Yet he retains a charming innocence. Likewise, where Japanese culture has often regarded menstrual blood as defiling, Tsuge transforms it into a thing of beauty – the red roses. And with all the dangers attendant on puberty, Tsuge leaves the girl safely carried on the strong but innocent shoulders of the little boy. The changes coming over her are as natural as the burgeoning vegetation around her – it’s a pastoral idyll, to set against the squalid lechery of urban sex depicted in other works by Tsuge. The disengagement of the “hero” is a puzzle – the story barely even needs him. He is far less involved than the young man in Numa. He just touches tangentially on this closed world.

SYMBOLS: Flowers, vegetation, fish, snakes.

* Numa. An English translation, calling it ‘The Marsh’, is available from Kotonoha. However, there are many serious translating errors in it.

http://s1.bakabt.com/154000-yoshiharu-tsuge-presents-marsh-torrent.html

Sorry Tom; my apologies that your comment got caught in captcha.